When the Coal Came: Imagining Life in South Wales as the Pits First Opened

Imagine it: the early 1800s, a quiet valley in South Wales, thick with forest, dotted with scattered farms and close-knit communities living off the land. Life was hard but familiar—rooted in rhythm, tradition, and place.

Then came the coal.

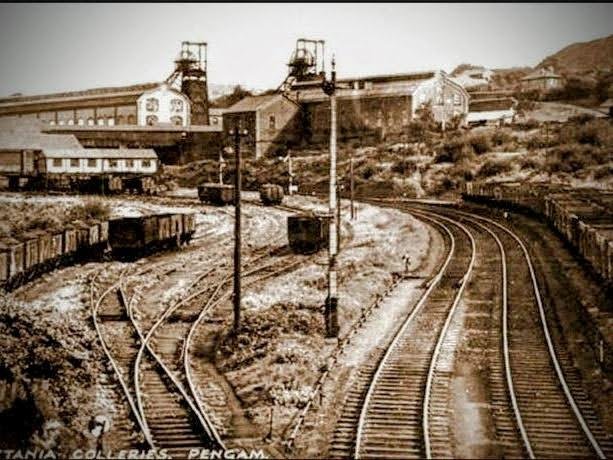

At first, it must have felt like a whisper—strangers arriving with talk of mineral rights and railways. Then the land changed. Hills were carved into, pits sank deep into the ground, and chimneys started to rise like warning beacons.

Who Owned the Early Pits?

In the beginning, much of the South Wales coalfield was in the hands of landed gentry. Two families stood out: the Butes and the Insoles.

- The Bute family, Scottish aristocrats who became some of Cardiff’s most powerful figures, invested heavily in docks and collieries. By mid-century, they controlled vast swathes of land and helped turn Cardiff into the world’s biggest coal-exporting port.

- The Insole family, originally coal merchants from Somerset, rose rapidly. James Harvey Insole opened his first colliery in the 1830s and would later run successful pits in Cymmer and Aberdare. Unlike the Butes, the Insoles worked closely with industrial development and were seen more as working entrepreneurs than distant landlords.

Where Did the Workers Come From?

By the mid-19th century, the South Wales valleys were booming. Pits needed workers—thousands of them. But the local population wasn’t enough.

So they came from Carmarthenshire, Pembrokeshire, and Mid Wales, walking miles in search of work. Many more came from England—especially Gloucestershire and Somerset. And later, during the boom years, Irish immigrants arrived in large numbers, fleeing famine and seeking hope underground.

The coalfield became a melting pot, with chapels and pubs filled with different dialects, accents, and songs. Communities had to learn to live together fast.

How Many Worked the Pits?

By 1850, the numbers were growing rapidly. Early collieries might have employed 50–200 men, but as seams deepened and technology advanced, this number swelled. By the 1890s, some South Wales collieries employed over 1,000 men. The Rhondda Valleys alone had more than 40,000 miners by the turn of the century.

Boys as young as 10 were sent to work as “trappers,” opening and closing ventilation doors. Whole families were built around the shift rota. The mine wasn’t just a job—it was life.

What Must It Have Felt Like?

For many locals, it was a paradox.

- Excitement—A new world was opening up. Coal brought money. Families who’d once scraped a living from sheep or smallholdings could now earn steady(ish) wages.

- Fear—Mining was dangerous. Early pits had few safety measures. Collapses, explosions, and flooding were all too common.

- Displacement—The land changed beyond recognition. Valleys that had echoed with birdsong and the slow rhythm of farming were now filled with the clang of metal, the blast of steam, and the endless grind of industry.

Some felt pride—South Wales was fuelling the world. But others, especially those who lost family to the pit, must have felt an unshakeable sense of loss.

Legacy

Today, only the scars remain. Pit wheels, converted heritage sites, and the proud memories of mining communities.

But it’s worth pausing to remember those first days—when coal came to South Wales not as a promise or a profit line, but as a storm that would change everything.