Miners' Fortnight Through the Eyes of a Colliery Family

“We waited all year for this.”

That’s what my father used to say, and I find myself saying it now, standing in line for the chip van outside our caravan at Trecco Bay. It’s July, the sun’s out, the wind’s salty, and it’s Miners’ Fortnight — the best two weeks of the year.

For families like ours, from the Valleys — Rhondda, Cynon, Merthyr, Aberdare — this was more than just a holiday. It was a ritual, a right, a reward for a year spent down the pits.

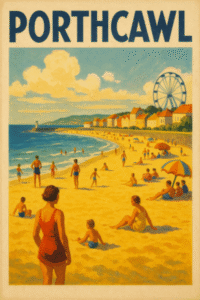

🏖 The Great Escape to Porthcawl

Each July, the collieries would shut for a fortnight. Not just one or two, but almost all of them. It was part of the industry calendar, and it meant one glorious thing — the whole community heading en masse to the seaside.

And Porthcawl was the place to be.

The town would swell with tens of thousands of us. At its peak, it’s said that up to 70,000 visitors would descend on the town during Miners’ Fortnight. That’s almost four times the town’s usual population. We came by bus, by train, and in later years by packed cars brimming with bags, buckets and spades, and Nan in the front seat with her flask of tea.

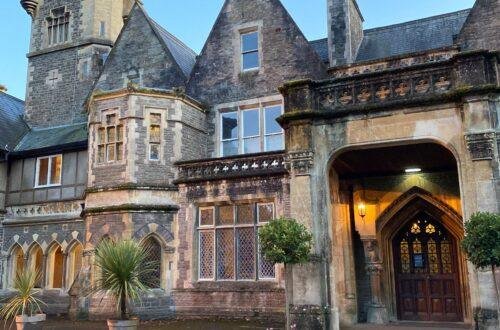

⛺ Life in the Caravan Parks

We stayed at Trecco Bay, one of the largest caravan parks in Europe. Back then, the caravans weren’t the sleek, luxury things you see today. Ours had thin walls, shaky steps, and a gas bottle outside that always made Mam nervous. But it had what we needed — beds, a kettle, and a roof over our heads just a short walk from the beach.

Everywhere you turned, there was someone you knew. Your neighbour from number 18, the milkman’s brother, or your cousin’s best friend from Tonypandy. It was like the Valleys had simply picked itself up and plonked itself by the sea.

You could walk through Trecco and hear a hundred voices — all Welsh, all lively. Radios blaring Tom Jones and Shirley Bassey. Kids squealing as they played cricket with driftwood bats. Mams hanging out swimming costumes on makeshift lines between caravans.

🎠 Seaside Joys and Simple Pleasures

Our days were simple. Up early (you never really stopped waking like a miner, even on holiday), bacon on the stove, then down to Coney Beach for the day. We’d ride the waltzers until we were dizzy, win plastic rings on the hook-a-duck, and spend our copper coins in the arcades.

Then there was the beach — golden sand, freezing sea, and the thrill of building a sandcastle big enough for your baby brother to sit in. Fish and chips were a must, vinegar-soaked and wrapped in yesterday’s paper. If you were lucky, a 99 from the van, the kind with the pink syrup if you asked nicely.

Evenings were for bingo, pints at the Hi-Tide, or family nights in the camp’s entertainment hall. We sang, we danced, and sometimes, we cried with laughter. You could feel the year’s weight melt off your shoulders.

🏡 A Community Tradition

Miners’ Fortnight wasn’t just about getting away — it was about being together. For two short weeks, we breathed in fresh sea air, shared stories under the stars, and reminded ourselves what we were working for.

The town welcomed us — grocers stocked up, pubs filled early, and the fairground buzzed like it knew we were coming. Porthcawl didn’t just host us. It became ours, and we became part of it.

💬 Final Thought

It’s hard to explain the magic of Porthcawl during Miners’ Fortnight to anyone who didn’t live it. But for those of us who did — those who spent July with sand between our toes and coal dust still in our skin — it’s a memory that never fades.

We came from the mines, tired and blackened, and for two weeks, we lived in colour.

The mines and other industries closed down for the last week of July and the first week of August, and resorts like Penarth enjoyed a surge of families that would visit the seaside for their summer break. Miner’s Fortnight became a vital part of the South Wales holiday scene during the 1960s.